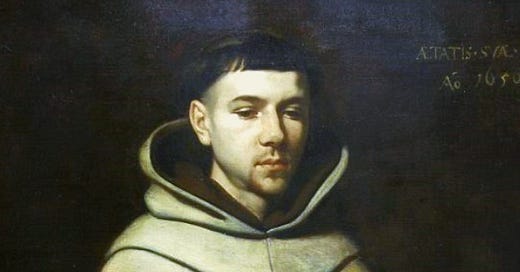

Was Saint John of the Cross Jewish?

Like his friend and fellow Carmelite Saint Teresa of Avila; Saint John of the Cross (often called by this name in Spanish; San Juan de la Cruz) is often cited as one of what we might call the ‘converso saints’ of the Roman Catholic Church with ‘converso’ referring to the fact that they came from so-called ‘New Christian’ families which meant they jews who had converted to Roman Catholicism either voluntarily, under pressure or forcibly in the Iberian Peninsula during and after the Reconquista.

Just like Saint Teresa of Avila, however, this claim is actually inaccurate and based purely upon speculation not evidence. (1) Despite this it is commonly simply claimed as being true without comment or further qualification in books on Saint John of the Cross. (2)

In this article I will address these claims and by way of beginning we need to know a bit about the man himself.

Saint John of the Cross was born as Juan de Yepes y Alvarez in 1542 in a small town of circa 5,000 people named Foniveros between the cities of Avila and Salamanca. (3)

His father was Gonzalo de Yepes who was an orphan from a good family (4) who was brought up by his uncles who were well-to-do silk merchants in the city of Toledo. (5) Other uncles and relatives of Gonzalo were high-ranking Catholic churchmen with four being canons of Toledo Cathedral, another an archdeacon of the collegiate church of Torrijos and a sixth an Inquisitor. (6)

So far so good but this is very information is often used to try and argue that Saint John was of jewish origins since as Brenan explains regarding the logic used in discussions of his alleged converso origins:

‘Such a family tree raises the question whether, like Santa Teresa of Avila, he may not have been of Jewish descent because so many of the canons of Toledo Cathedral were New Christians, while the silk trade had for a century and longer been almost entirely in their hands. This had more than a pedantic interest because in those days the misfortune of having Jewish blood in one’s veins was apt to impart a sense of guilt which could deepen the religious consciousness by giving it, as it were, a double dose of original sin.’ (7)

The problem is this is all pure conjecture and based upon the unsustainable assumptions that because canons of Toledo Cathedral were not infrequently of ‘New Christian’ origins and the silk trade – of which his uncles were part – was a largely ‘New Christian’ undertaking this therefore means that Saint John was of converso and thus jewish origins.

We then end up with a frankly weird situation of circular logic where Saint John is conjectured to be jewish without any documentation of that fact in the evidentiary record and then Saint John’s works are read as ‘inspired by his jewish origins’ – a fact which as Roth notes is simply absurd as you cannot tell biblical influence from jewish influence even granting this logic is true – (8) which is then used as ‘evidence’ to buttress these dubious allegations of Saint John’s jewish origins.

Since as Brenan rightly remarks all this is all based on assumptions not evidence (9) and he further simply points out that:

‘No proof of the Jewish origins of the Yepes family has come to light.’ (10)

Thus, we can see there isn’t any actual evidence and the ‘argument’ that Gonzalo was from a jewish family is based on nothing but speculation. Indeed, it is very similar to the entirely speculative argument made for famous Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes being of jewish origins and the same issue applies since to quote my not dissimilar point in regards to the claim:

‘Juan's father (Cervantes' great grandfather) was a cloth merchant in Cordoba. The problem, and the probable origin of the 'jewish ancestry' theory, is, as Bryon states, 'Cervantes' grandfather was in a converso's trade in a convert's town.'

Essentially Cervantes' paternal great grandfather was in a trade dominated by jewish converts to Christianity in a city that had only relatively recently converted from Islam to Christianity. The problem with this however is that it is precisely what the statement suggests: an assumption without evidence. Not all cloth merchants in Cordoba were jewish - although many were - and nor were those who weren't necessarily Islamic.’ (11)

In essence then – as with Cervantes - there is no actual evidence that Gonzalo had any jewish ancestry at all just wishful thinking, but also interestingly this is directly contradicted by another camp of historians who wish to claim Saint John was of jewish ancestry. Since they instead claim Gonzalo was from a respectable ‘Old Christian’ (i.e., Christians who weren’t converted from Judaism or Islam) who married an orphan of converso (i.e., jewish) origin named Catalina Alvarez: Saint John’s mother. (12)

Discussing this and the similar allegation that Catalina was actually a morisco (i.e., a Christian converted from Islam) not converso. Thompson explains at length that all these arguments are simply ludicrous, purely speculative and have been contradicted by subsequent academic research on the socio-religious dynamics of the geographical area concerned:

‘The dangers of building elaborate hypotheses on insecure foundations are well illustrated by the tendency among some scholars to stress the converso or morisco origins of Catalina de Yepes. While working in the grounds of his priory in Granda, Fray Juan is reported to have been greeted by a passer-by with the observation that he must be the son of ‘labradores’, workers of the land, to be so busily engaged. He replied that he was not: ‘Hijo soy de un pobre tejedor’, ‘I am the son of a poor weaver.’ The remark, if accurately remembered, is not as innocent as it seems. ‘Labradors’ were thought of as cristianos viejos, coming from pure Christian stock, untainted by Jewish or Moorish blood, whereas weaving was an occupation associated with cristianos nuevos. Was Catalina a morisca? Was this the stain on her reputation which caused the family of Gonzalo de Yepes to repudiate him on his marriage to her?

Recent historical research has shown that the morisco population of La Morana has been overestimated, and in any case had suffered a process of acculturation which made moriscos increasingly indifferent to and ignorant of their own religious inheritance. During Juan’s childhood Inquisitorial pressure, always present, increased around Medina and Arevalo as the result of a suspected resistance group active in the area. But mixed marriages were extremely rare, especially in the first third of the century, and out of the question between an old Christian of some family means and a poor morisca. The claim that Catalina and her family had friends who were moriscos is not borne out by examination of the 1565 records either, since none of the names mentioned in this connection appear there. These factors strongly suggests that the stain of social inferiority and poverty was the true reason for the reaction of the Yepes family to Gonzalo’s marriage, if the story has any truth.’ (13)

In summary then we can see that proponents of the claim that Saint John was of converso ancestry are trying to have their cake and eat it too. Since one set of proponents claims Gonzalo not Catalina was of jewish origins based on his family’s professional success and other set of proponents claims Catalina was of jewish origins but Gonzalo wasn’t but rather was an ‘Old Christian’ whose family repudiated him because he married a ‘New Christian’.

The likely reality is of course that – as mixed marriages between ‘Old Christians’ and ‘New Christians’ were extremely rare in the area – that Gonzalo and Catalina were simply both ‘Old Christians’ and that the reason for the rejection of Gonzalo by his family was Catalina’s poverty and social status. Since she was a poor orphan who was earning her keep as a silk weaver when Gonzalo met and married her; (14) only to then die suddenly a few months after Saint John’s birth leaving Catalina and her children in the direst poverty. (15)

If we further add to that the evidence that Saint John’s earliest biographers from which we get most of our biographical information about him explicitly believed him to be – and stated as such - an Old Christian. (16)

Then we cannot but conclude that the claim that Saint John of the Cross was from a converso family and was thus of jewish heritage is a complete and utter myth based on no actual evidence whatsoever.

References

(1) On the myth of Saint Teresa of Avila’s alleged jewishness see my article: https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/was-saint-teresa-of-avila-jewish

(2) For example: Desmond Tillyer, 1984, ‘Union with God: The Teaching of St John of the Cross’, 1st Edition, Mowbray: Oxford, pp. 3-5 and Norman Roth, 2002, ‘Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain’, 2nd Edition, The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, p. 157; on this being common see Colin Thompson, 2002, ‘St. John of the Cross: Songs in the Night’, 1st Edition, SPCK: London, p. 28

(3) Gerald Brenan, 1973, ‘St. John of the Cross: His Life and Poetry’, 1st Edition, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, p. 3; Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 27

(4) Brenan, Op. Cit., p. 3; Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 28

(5) Brenan, Op. Cit., p. 3

(6) Ibid., pp. 3-4

(7) Ibid., p. 4

(8) Roth, Op. Cit., p. 413, n. 1

(9) Brenan, Op. Cit., p. 95

(10) Ibid., p. 4

(11) https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/was-miguel-de-cervantes-jewish

(12) Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 28

(13) Ibid.

(14) Ibid., p. 27; Brenan, Op. Cit., p. 4

(15) Brenan, Op. Cit., p. 4

(16) Thompson, Op. Cit., pp. 24-25