The Protocols of Zion: Myth, Libel and Fact

The Real History of the Most Controversial Anti-Semitic Document of All Time

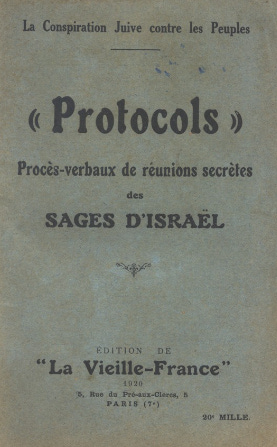

Possibly the most controversial area in the whole of the study of anti-Semitism and the charges that it makes against the jews is the study of what has come to be called 'The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion'. Before I began writing this article I did - in fact - hesitate for a few minutes to think about whether I should write a preliminary defence of them on the basis of the multitude of studies of this small inflammatory book that have appeared or not.

However as much as I consider myself to be in the anti-Semitic agnostic tradition on the Protocols - with people like Joseph Goebbels, Arthur Keith Chesterton, Revilo Oliver and William Pierce - I do think there is actually a good case for arguing that the Protocols are not as 'absurd' and 'intellectually stupid' as angry academic jews with an axe to grind - like Stephen Eric Bronner - (1) argue.

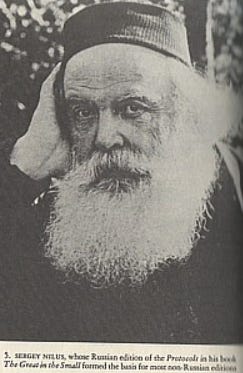

I would point out that while I don't consider the Protocols to be the 'key to world events' - which as Chesterton pointed out is an intellectually lunatic position (2) and is fodder for the likes of Bronner and Ben-Itto - I do think there is now a reasonable case to put forward for the document's original authenticity and also that it was actually meant to be a 'world plan' of a sort, but that the original document was subsequently mutilated and redacted by its later publishers - particularly the infamous Russian mystic Sergei Nilus - as well as being badly translated (3) which has led to a plethora of denunciations of the Protocols as fake based on alleged and actual problems with the text.

I will here reiterate that this is merely a preliminary essay to a book length defence of the Protocols that I am now in the process of publishing as well as that this is a written indication of some of my conclusions as of this moment as stated in my 2012 radio appearance with Deanna Spingola. (4)

To make this article easier to read and refer to back to I have opted to split up each part of the case into its own self-contained section.

Now - as Revilo Oliver declared- forward to the abyss!

The Many Lives of the Protocols of Zion

One of the many myths that circulates about the Protocols of Zion is that the text we have reached us fully formed and has not been altered in transmission: this is true both of anti-Semitic (5) and philo-Semitic work (6) on the subject. Even the attempt of the famous jewish cartoonist Will Eisner - which included a foreword and afterword from authors on the subject (Eco and Bronner respectively) - did nothing to disabuse the notion of this complete transmission and repeated the myth - (7) in spite of citing specialist works by authors such as Cohn and de Michelis who have written extensively on the formation of the Protocols - as well as the century old conspiracy theory that the Okhrana office (the Tsarist secret political police) in Paris had deliberately forged the text to induce Tsar Nicholas II into a belief in a mass jewish plot against his throne, (8) which incidentally he didn't actually need any help in believing. (9)

Now as I have stated this idea of a 'complete transmission' is a myth as we know of numerous differences between the editions, but a detailed linguistic and textual analysis of this has only been attempted recently by de Michelis. (10) I here summarise the transmission into chronological format correcting Levy's erroneous version (11) that is based on the a priori assumption of the truth of the theory of the Okhrana office in Paris being the originator of the Protocols based directly on Cohn's oversubscribed argument on this point, which the CIA's historical analysis of Paris Okhrana's operations notably criticises by simple omission (in spite the fame and age of the hypothesis). (12)

The chronology of the Protocols of Zion should read thus: (13)

Late 1901/1902: Original document discovered/written/created. Mikhail Menshikov mentions the existence of the Protocols in 'Novoe Vremya' ('The New Times') in April 1902.

1903: Publication of original Protocols in 'Znamia' ('The Banner') by Pavel Krushevan in a series of seven instalments beginning in September.

1904: Partial republication in the third edition of Ljutostansky's 'Talmud I everi' (cleared for publication by censor on the 3rd November 1903), this includes the first suggestion of a link to Zionism.

1905: Sergei Nilus publishes a longer and heavily edited version of the Protocols as an appendix to his book about the coming of the Anti-Christ: 'Velikoe v Malom' ('The Great in the Small') in addition to three anonymous editions which are shorter than Krushevan's original that date from this time. Introduction of Freemasonry into - and the removal of Old Testament references from - the text.

1906: Georgi Butmi de Kacman publishes a different version of the Protocols as an appendix to the third edition of his book 'Vragi Roda Chevlovecheskago' ('Enemies of the Human Race') (preface is dated 5th December 1905).

1907: Georgi Butmi de Kacman publishes a slightly re-edited version of the Protocols as an appendix to the fourth edition of his book 'Vragi Roda Chevlovecheskago' ('Enemies of the Human Race').

1911: Sergei Nilus re-publishes his book 'Velikoe v Malom' ('The Great in the Small') in a second edition: no substantial change to the Protocols text.

1912: Sergei Nilus re-publishes his book 'Velikoe v Malom' ('The Great in the Small') in a third edition: no substantial change to the Protocols text.

1917: Sergei Nilus re-publishes his book 'Velikoe v Malom' ('The Great in the Small') in a fourth edition: a substantial change to the Protocols text and the beginning of the attribution of the Protocols to Theodor Herzl.

This chronology clearly demonstrates two key issues:

Firstly, that the first mention of the Protocols occurs early in 1902, while the first text we have of the document itself comes from 1903 as well as how the Protocols began to be redacted and added to as early as late 1903/early 1904 and how they continued to be added to and changed.

Secondly that the edition that is popularly reproduced comes from the fourth edition of Sergei Nilus (in 1917) and which has been subsequently revised in some quarters by the use of the first edition of 1905.

This thus informs us that contrary to the received popular wisdom on both sides of the argument: we are in fact dealing - in terms of the common version - with a composite document that has been changed by different authors until a 'definitive' version (of the document and its origins) happened to be created largely by the accident of Ludwig Mueller von Hausen (whose nom de plume was Gottfried zum Beek) having brought it back to Germany and publishing it there – allegedly - through the Thule Society. (14)

Now clearly, we are faced with a problem in the orthodox account of the Protocols once we recognise that we are dealing with different traditions and versions of the same document, because many key arguments against the Protocols - such as the Joly plagiarism assertion and the internal 'contradictions'/'absurdities' - lose much - and indeed frequently all - of their explanatory power.

You might ask why is that?

Well, put simply if we are dealing with a complete transmission of the original document then we can reasonably place it under the analytical microscope to see how it holds up to sceptical scrutiny. However, we cannot place that document under the analytical microscope if we do not know or cannot use its original form precisely because if we are not dealing with the original then we are only dealing with an edited or changed edition of that document: so, we cannot criticise - let alone disregard - the original document because we have analysed a substantially altered later version of it.

Instead, the process must necessarily be to reconstruct and/or obtain a copy of the original document so that we can work with that as otherwise we are dealing in inconsistent intellectual propositions in terms of trying to negate the issue of edition and text in attacking the original by a later version (rather like trying to analyse a wolf by analysing a breed of dog instead).

Some might object here and argue that what anti-Semites use is this later edition and while that is indeed true: (15) it is an invalid argument in so far as it is arguing that because anti-Semites - as well as critics of the jews in general - have incorrectly used the later edited text to try to explain world events. (16) It is thus fine for jews to use that same text to 'disprove' the original document in spite of their tacit (and sometimes even open) acknowledgement - by citing work which informs them in detail of this problem - that the document they are actually attacking is not that original document.

This attitude is thoroughly intellectually dishonest and is personified in the work by Alex Grobman who uses Cohn to 'prove' that the 'primary author' of the Protocols was Matthieu Golovinsky (a journalist somewhat linked to the Paris office of the Okhrana) while not mentioning the issue of multiple editions: (17) instead Grobman appears to be using the 'primary author' notion to imply the age old plagiarism and anti-jewish conspiracy meme that actually pre-dates any evidence at all that would suggested such a theory. (18)

We therefore have to conclude that because the original document is not the one that is actually being criticised - especially as most start from Nilus' 1905 edition which contains a significant number of major variations - in nearly all literature on the Protocols: we cannot admit any argument for or against the Protocols' authenticity without clarification of what the original text actually said.

We can demonstrate the futility of criticism based on these later editions by pointing out several major issues with using later versions of the Protocols as Cohn's study and the many who have followed him do. (19)

To wit:

A) The text of the Nilus edition is significantly longer when compared to the Krushevan edition. (20)

B) The amount of allegedly 'plagiarised' material (as a percentage of the total) substantially increases in later editions, but the most notable jump is from the Krushevan edition to the Nilus edition. (21)

C) There are Old Testament references and quotes in the Krushevan edition that are simply omitted in the Nilus edition. (22)

D) There is no mention of Freemasons in the Krushevan edition, but these are numerous in the Nilus edition. (23)

E) The Krushevan edition is not divided into Protocols while the Nilus edition is. (24)

F) The Krushevan edition contains numerous Ukranianisms and clarifying sentences that the Nilus edition omits. (25)

We can see therefore the significant problems of using the Nilus text as a basis for 'debunking' the Protocols of Zion as Jacobs and Weitzmann have tried to do (26) in the tradition of earlier jewish partisans like Segel (27) and Bernstein. (28) Therefore, we can suggest that any attempt to 'debunk' or confirm the Protocols based on the existent translations cannot be correct as there is as yet no foreign language translation of de Michelis' Russian language reconstruction (or a peer review of that reconstruction).

We can further assert that the details of the Krushevan edition of 1903 suggest to us that the 'explanation' for origins of the Protocols in offices of the Paris Okhrana is thrown into deep doubt as de Michelis has beautifully demonstrated. (29) I cannot however concur with de Michelis overly respectful treatment of the 'Paris Okhrana' hypothesis precisely because it pre-dates any evidence to suggest it (30) (a tantalizing suggestion - which de Michelis has overlooked - of which is found in Bernstein's introduction to the memoirs of Mendel Beilis) (31) and also bases itself on three testimonies all of which we have significant reasons for doubting the veracity of. (32)

The Problem of Paris

That the Protocols of Zion originate from Paris has been the central element of the myth that surrounds them in so far as it purports to explain where they have come from (33) and also why they are important (as Paris was at this time a major centre of jewish life in Europe). (34) This explanation has been utilized by both sides of the debate, which are best described by juxtaposing them into two different majority propositions:

Philo-Semites and jews portray the alleged events of Paris - dating them to between 1894 and 1897 - as being when an anti-Semitic conspiracy by the Station Chief of the Paris Okhrana Peter Rachkovsky decided to try to gain favour in the Russian court for their views by 'uncovering' a document forged by an exiled Russian journalist named Matthieu Golovinsky that proved beyond doubt the truth of the contention that there was a jewish conspiracy against Russia. (35) This was however not circulated at court for reasons that are not made clear by this theory's proponents let alone suggesting reasonable evidence for their case other than 'coincidence' and the detective principle of cui bono (who benefits).

Anti-Semites - as well as some anti-Zionists who maintain a strong anti-Zionist line - (36) portray the events of Paris - dating them to between 1894 and 1897 - as being when either a jewish double-agent - Schorst or Efron - (37) for the Okhrana infiltrated and stole the Protocols from a Masonic Lodge in Paris in 1894/1895 or the First Zionist Congress of 1897 (it is sometimes suggested that they were stolen from Herzl's private belongings) or a long-time Russian expatriate in Paris - Madame Justine Glinka - (38) stole them from a jew of her acquaintance. These were alternatively either transmitted to Russia where they were promptly filed and/or brought back to Russia by Major Alexander Sukhotin who then had them published through the auspices of General Stepanov and Sergei Nilus on his return. (39)

Both these versions of events - established by three very different witnesses (two for the former and one for the later) - seem to point to a French - and more particularly a Parisian - origin for the Protocols: don't they?

The problem with this is actually deceptively simple in so far as we are dealing with three witnesses who unfortunately don't seem to know anything about the document that they are talking about. They contradict each other, produce impossible timelines and appear sometime after the Protocols have become famous in addition to having in each case easy to discern motivations for claiming to be an 'unknowing witness' (to use de Michelis' terminology).

The first witness we need to interrogate is the most famous of all Protocols witnesses - as it is from her that the anti-Protocols timeline is derived - Princess Catherine Radziwill. Radziwill was a rather eccentric Polish princess, author of numerous books before, during and after the Bolshevik revolution, an obsessive-compulsive and also an occasional white-collar criminal. (40)

Radziwll claims that she saw either the edition of Ljutostansky or Nilus - which we can discern from her dating - in 1904 or 1905 in the offices of the Paris Okhrana and she names Rachkovsky and Golovinsky as being the principal architects. (41) However, as Burcev pointed in 'La Tribune Juive' in 1921: she wasn't in Paris at the time! (42)

Some following Cohn try to negate this chronological issue by asserting that Radziwill was simply mistaken years after the fact and try to buttress this by pointing out that both Radziwill and du Chayla say they saw a document on yellowish paper, with an ink stain and different handwriting. (43) This is indeed true, but such a coincidence between two witnesses who differ on all other details cannot be admitted for the simple reason that we have no proof they even saw the document in the first place other than their say so.

Besides the description - as others have to my knowledge have failed to note - is not very specific: it is very general and as such could have easily been conceived of independently and been just a happy coincidence for Protocols 'debunkers' like Lucien Wolf: who was already championing the idea of anti-Semitic conspiratorial origin of the Protocols from the Paris Okhrana before there was any actual evidence for it. (44)

In addition we have to remember that Radziwill does not have a good character - she was after all a convicted criminal and an obsessive-compulsive - and that as much as some may want to believe her testimony as it confirms their pet theory; we cannot hold her to be anything but a dubious source at best. After all the question must be: why did she wait so late to 'remember' all that she did and why could she recall such general details of yellowish paper, ink stains and different handwriting but then get the year she allegedly saw it out by a decade?

Now what if Radziwill is somehow telling the truth and she saw an edition of the Protocols (which she identifies as either the 1904 or 1905 edition) in the office of the Paris Okhrana?

Now we know she was unaware of the 1903 publication, and this therefore puts pay to the notion of her having seen an original copy, but at the same time it is also quite reasonable to suggest that she saw the Ljutostansky or Nilus edition: especially when we remember that Ljutostansky's work was actually a source book on anti-jewish literature and was frequently published with updates. This would neatly explain Radziwill's claim without disregarding it and also answering the issue of how Radziwill knew that the document she generally describes was the Protocols (as the Protocols title and linkage to Zionism - which she mentions - had now come into use).

Thus, even if we wish to admit Radziwill it is obvious that she is not a reliable source and that her testimony can be explained in a more plausible alternative scenario that to my knowledge has not been explored by any author on the Protocols.

The second witness we need to interrogate is Armand Alexandre de Blanquet du Chayla who is a somewhat mysterious French nobleman who spent a lot of time in Russia in early twentieth century. Now as I have above suggested by implication: du Chayla is the key piece of the puzzle in that it is he and nothing else that is used by Cohn to build his theory of the origin of the Protocols in the Paris office of the Okhrana.

Unfortunately for Cohn and the many others who argue this hypothesis du Chayla is far more problematic than even Radziwill in so far as he claims to have seen Nilus' 1905 version in 1901 when Nilus was introduced to the Russian court. The problem with that is that we definitively know that Nilus' version was published in 1905 not 1901 and that Nilus was introduced at court in 1905 not 1901. Further du Chayla's account of Nilus replacing another mystic - one Phillipe - at the Tsar's court places the incident definitively in 1905. (45)

Among other things du Chayla reproduces an account of the travels of Nilus going to Germany - commonly vapidly attributed following Cohn to a 'lapse of memory' - (46) in late 1918 to early 1919 is actually the account of Nilus' son. (47) This is all dubious enough given the fact that du Chayla is supposed to corroborate Radziwill and this scale of divergence and general inaccuracy is simply unacceptable in sources central to an already speculative theory.

However, there is another problem with du Chayla in that he seems to have been an agent of the Soviet Union at least as early as 1919 when he was expelled from the Crimea by General Wrangel for being a Bolshevik agent (48) and the only reason he was not summarily shot was because he was a French citizen. (49) Given the centrality of du Chayla's testimony and the work done by Soviet archivists (as well as the pro-Bolshevik jewish author Alexander Tager) to try and find proof for it: (50) it is quite likely - as de Michelis concludes - that du Chayla had been 'put up' to his Protocols testimony by the USSR's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (he was accused of working for Georgi Chicherin the head of this ministry at the time by General Wrangel). (51)

In case the reader thinks that I am here suggesting that du Chayla's story regarding Nilus is made from whole cloth: we do know that du Chayla did know Nilus for a time, (52) but the fact that du Chayla makes his mistakes in and around the Protocols as well as that he waited till 1921 to come forward with his testimony (and also singularly implausible story of how he came to 'notice' the Protocols and write his testimony [suggesting that he had been directed towards the rapidly selling Protocolss]) point to a Soviet involvement in 'debunking' the Protocols . (53)

Then we have to conclude that not only is du Chayla dishonest, but in fact we can establish with a reasonable level of certainty that he is acting in the interests of a government trying to manipulate the Protocols and later the Bern trial with misinformation directed against the forces of radical right, which we know was Soviet policy at this time. (54)

We also know of a parallel usage by Soviet propagandists of manipulating events such as this to suit their propagandistic needs of the moment, (55) which again suggests; although detailed research is still required, that we are dealing here with a Soviet propaganda ploy and not a serious witness for the Protocols being forgery.

A fact which largely discredits the Bern Trial of 1934 as an argument precisely because du Chayla is the central 'witness' that links the Protocols to the Russian Okhrana after Radziwill's testimony was judged by the court to be heavily flawed.

The third witness we need to interrogate is the only anti-jewish one that we have: General Philip Stepanov. Stepanov offered pivotal; although flawed testimony, that an anonymous lady (Madame Justine Glinka) (56) received the Protocols from a jew (alternatively Efron or Schorst) who then passed them to a retired Russian major named Alexander Sukhotin (57) who then passed them on to Stepanov who published them independently in 1897. (58) Normally such a wild sequence of events would be quickly dismissed if Nilus had not independently confirmed that he received his copy from a retired Russian major named Sukhotin. (59)

De Michelis clearly identifies that here we find numerous issues with chronology as in the first instance: we have no evidence other than that reported by Henri Rollin of an actual edition of the Protocols before 1903 and even then, we certainly do not have a copy of them. De Michelis' suggestion that we identify the Stepanov edition with one of those produced in 1905 is a sensible one given that Stepanov contradicts every other known source we have in regard to an alleged French origin in so far as he dates them as being published before the first Zionist Congress in that same year.

This contradicts the Zionist origin of the Protocols that was attached by Ljutostansky and Nilus to them: indeed, I would argue that because Stepanov's testimony comes from 1927; (60) it is not unreasonable to suggest a cross-pollination of his testimony from the later attribution of the Protocols by Nilus to Herzl in 1897, which was then popularly supported by Mueller von Hausen and Fritsch among others. I will also note that although we have circumstantial evidence of the origin from Sukhotin we should bear in mind that we have no evidence - and indeed good evidence against - the transmission from Glinka. (61)

That evidence is fairly simple: we know Glinka was fluent in French and Russian, so why then would she write Russian with Ukrainianisms that we have innumerable examples of in the original Krushevan edition of the Protocols from 1903? As Glinka was not from the Ukraine: the evidence is very much against her having been the conduit for the Protocols let alone the fact that she is usually alleged to be the French to Russian translator of them. (62)

In spite of these problems and contradictions within contradictions that Stepanov's testimony causes in our chronology: Rollin has pointed out that Stepanov quite unintentionally gives us the origin of the legends of Rachkovsky's involvement in so far as he had been made a Superintendent of Police in 1905 and as such seems to have been involved in spreading the Protocols but not in creating them. (63)

This then gives us some idea of the mythologizing process behind the theories regarding the origins of the Protocols of Zion as it gives us the basis of most anti-jewish (64) and pro-jewish (65) arguments for locating that origin in Paris.

As we can see these three pieces of witness testimony are weak and/or dubious sources for a Parisian origin of the Protocols and indeed the strongest of the three – Stepanov - contradicts nearly all the interpretations as to origins that are given in the literature. It is clear then that without these witnesses we cannot have a French origin of the Protocols.

However, before we leave the problem of a Parisian origin: it is important to explain the absurdity of locating the origins of the Protocols of Zion in the Paris office of the Okhrana.

The problem for the 'anti-Semitic conspiracy from the Paris Okhrana' argument is a fairly elementary one in so far as it tries to make a complex internal political situation into a simple one of anti-Semites and jews. It reduces two factions who were actively conspiring against each other (the pan-Slavists and the pan-Russians [the latter is a more jingoistic and extreme variant of the former]) to obtain power and influence into two factions that were working hand in hand to help each other politically so they could blame the jews when in fact they were bitterly fighting each other in a power struggle. (66)

I would propose that this is the reason why when you read the literature on the Paris Okhrana: one notices a distinct lack of belief (through lack of mention) of the well-known theory as to the origins of the Protocols of Zion in that same organisation. I suspect that while the authors on the Okhrana don't disbelieve it: they also don't believe it as it goes contrary to their knowledge of the Okhrana's internal politics, which could in turn destroy the most popular and most viable thesis against the authenticity of the Protocols as a document (and therefore open them up to potentially being genuine).

The fact that Rachkovsky's involvement has now been established by Rollin to be later in the history of the Protocols (i.e., in 1905 not in 1894-1897) explains why his name came up in the witness testimony as he would have been associated with Nilus at about the same time, we know du Chayla was.

As du Chayla would have likely known of Rachkovsky's status as the former head of the Okhrana operation in Paris and also of Rachkovsky's involvement in distributing them in 1905. We may propose that du Chayla simply put two pieces of information from his time with Nilus together to create a plausible story as he knew Rachkovsky had been in Paris at the head of the Okhrana there but would not have known when he had returned which he dated to several years before he met Nilus to create plausible linkage in the Protocols story.

There I think we have the origin of the story of the Protocols in the Paris Okhrana: a myth created on a mistaken assumption by a witness who was serving as an agent for the Soviet Union and whose words fitted into early debunks of the Protocols at this time, which has allowed the origin of the Protocols in the Paris Okhrana to become an accepted theory albeit; as I have outlined, one that has little to no substance to it whatsoever evidentially.

The Satirical Origins of the Protocols?

The inevitable question on the reader's mind; after having removed the evidence for a French and more specifically Parisian origin for the Protocols is: where do they come from then?

Well, the simplest answer is in fact the right one: the Russian Empire. We can see this in so far as we do not have a copy of the original Protocols from 1903 or before in any other language but Russian.

After all, if there is no French original - as de Michilis rightly asserts - (67) then all that is left is a document that came out of Russia in 1903 and was first mentioned in April of 1902. If we understand this then we realise that the question of the authenticity of the Protocols is actually thrown wide open again (rather than being simply a minority theory), as here we have a document whose alleged back-story we know to be very likely false and whose origins are in the country it was supposed to be particularly plotting against.

Now I don't doubt some will - and indeed some have- seized on this revelation to argue that the Protocols is a 'crude anti-Semitic hoax' originating from Russia at a time of great upheaval and insecurity. (68) Now the problem with that argument is quite fundamental in that it assumes that because the Protocols are now revealed to come from the Russian Empire not France and/or Paris; they are ispo facto a hoax.

There is no reason for drawing such a quick and I would say illogical conclusion for the simple reason that no longer is the Protocols ascribed to the First Zionist Congress or to a theft from a Masonic Lodge in Paris, but rather to a country where jews were openly organising propaganda and revolts against the government and more particularly were as a group solidly against it. (69)

This means then that the theory that a jewish origin of the Protocols is actually just as simple as a solution - if we use the logical principle of Occam's Razor - as an anti-Semitic origin of the Protocols. This then removes some of the most rhetorically effective arguments against the Protocols by placing them not as a Masonic or an international Zionist document, but rather as a local document to the Russian Empire, which both explains the document's focus on Russia and also some of its very Russian characteristics that have long been used to attack it. (70)

Now if we factor in that the original Krushevan edition of the Protocols in 1903 had numerous Ukrainianisms within it: we can with de Michelis link the Protocols to either the Ukraine or the Ukrainian diaspora. (71) This again might be used as evidence of a 'crude anti-Semitic hoax' but I think it is important to understand that this particular time in Ukrainian history is the right time and right place for a conspiratorial document of this kind for both theories of a jewish or anti-jewish origin of the Protocols. Precisely because this is a time when feelings against the jews were running high, there had been recent local pogroms against the jews for real and imagined offences (72) and there was a strong undercurrent of both Zionist and Marxist radicalism in the jewish community itself. (73)

It was a time of change and flux: when moderate solutions were out, and radical solutions were in.

This was the ideal time for a Protocols-type document to be created by either jews or their opponents.

De Michelis, for example, tacitly recognises this problem for the anti-Protocols argument when he seems to be in an internal contradiction himself: he wants to argue the Protocols are an anti-Semitic hoax from the Ukrainian diaspora, (74) but he also knows that much of his case is speculative and that he has severe problems putting a person's name or organisation's name to the origin of the Protocols. So as a stopgap measure, he claims that Cohn's theory of the origin of the Protocols being from the Paris office of the Okhrana is actually an 'evidence-based theory' (75) while having just demonstrated that it actually isn't one. (76) After all, on the back of the same logic he uses to defend Cohn he would have to concede that Fry's theory of Asher Ginzberg (pen name Ahad Ha'am) being intimately involved was similarly 'evidence-based' which he is loath to do.

De Michelis' argument is based on the idea that because we know that Menshikov, Krushevan and Butmi were all associated with each other and did have contacts in the Ukraine: (77) that it must have been one of their contacts who wrote it, which would - to be intellectually equitable - account for a lot of the evidence, but I would point out that it doesn't account for several issues that de Michelis has overlooked.

Firstly, de Michelis ignores the problem of why the Ukrainianisms were kept in a document that was published in a Russian newspaper and why they were then edited out in 1904. The problem there is that if this was a Ukrainian anti-jewish writer who had written a 'satire' on Zionism - which is what de Michelis argues it was - (78) for 'Znamia' then why did Krushevan not edit them out as was the usual journalistic practice? After all they are not integral to the document itself: so why leave them in and make the 'Learned Elders' into proverbial country bumpkins (thus disrupting the satirical intent)?

I point to this particularly because de Michelis' suggested developmental chronology hinges on the unpolished nature of the Protocols and the fact that they were originally intended to be a satire - based on a somewhat trite reading of Menshikov's article of April 1902 - which is made nonsense of when we understand that the 1903 version of the Protocols does not include any 'in the know' references to them as a satire and as such we are forced to ask the fundamental question of why keep such obvious problems for a reader (i.e., Ukrainianisms would not have been pleasant or easy reading for most Russians) in a document merely meant as a 'satire'?

De Michelis ignores this and instead focuses on the alleged connections between Menshikov's article - which he suggests is an 'in the know' wink that could be read as such by others (but offers no meaningful substantiation of this allegation) - (79) and the Krushevan's original 1903 edition of the Protocols. This is obviously problematic as it entails reading Menshikov's article from a priori conclusion in that if you read it as an article believing it to be a coded message of a sort in order to agree with the conclusion: rather than taking a more literal reading of Menshikov as indicating that he has knowledge of a jewish secret document that might shed insight into what is going on. This is I think a more accurate reading of Menshikov's article and does not require reading too deeply into what Menshikov is saying without any evidence to support such an overly-complex interpretation.

Secondly one has to wonder why - if a Ukrainian friend of Menshikov's and Krushevan's wrote the Protocols - it appeared under Krushevan's name rather than their own or perhaps more appositely: why did the Protocols appear with a commentary from Krushevan rather than the original Ukrainian author?

The problem here is central to de Michelis' argument in that if we have a Ukrainian anti-jewish author writing the Protocols: why do we not know who they were and why they originally wrote them? De Michelis' theory of it originally being a 'satire' cannot hold precisely because it assumes intimate collaboration between three different parties on a single document over; presumably, nearly two years (which he has insufficient evidence for) and that it is 'satire' seems manifestly unknown to Krushevan whose commentary on the Protocols is predicated on their authenticity.

Also we have Butmi - an editor of the Protocols himself three years later - to contend with in so far as de Michelis' asserts he was part of the same circle as the said Ukrainian, Menshikov and Krushevan, but then offers no reasoning as to why Butmi would not have known that the Protocols were not genuine when he included them in the third edition of his book 'Vragi Roda Chevlovecheskago' as piece of evidence to support his case.

This then leads us onto the third problem with de Michelis' proposition in so far as it is manifestly absurd as it necessarily implies that these men - who let’s not forget knew each other - were either deliberately propounding a 'satire' as a real document (i.e., they were being malicious) or they were taken in a 'crude hoax' (i.e., they were being foolish). De Michelis has no actual evidence for either suggestion, but makes them anyway and seems to believe that they are inherently valid because the Protocols are - in De Michelis' characterisation of Jouin's argument - a 'true forgery'. (80)

In essence then de Michelis commits the cardinal intellectual sin of assuming the Protocols are fake a priori - although I am sure he would argue that this has been 'proven' by the alleged 'plagiarism' - (81) and that this therefore in typical circular logic means that anti-Semitic Russians and/or Ukrainians must have written them. De Michelis is effectively saying then that because he knows the Protocols are fake, we know that they are fakes and have to focus on who wrote them!

De Michelis' argument is then intellectually absurd and as such needs to be discarded. I would also note in passing that because de Michelis well-knows that the 'alleged plagiarisms' are problematic (as they usually refer to the later Nilus and not the original Krushevan edition) and that the Protocols likely originally come from the Russian Empire not France: he is trying to - as he puts it - 'square the circle' for another anti-Semitic conspiratorial origin rather than re-opening the question of the authenticity of the Protocols as his evidence and analysis otherwise require.

This is - to use a metaphor - de Michelis' guilty little secret of course as having destroyed nearly a century of anti-Protocols literature and arguments he likely well realises that the authenticity of the Protocols is now once again arguable and thus he has done something that few to my mind could possibly do: give the Protocols of Zion a new lease of life. Hence de Michelis' almost habitual attempt to attribute them to anti-Semites rather than even consider any kind of jewish authorship, which incidentally other Protocols scholars such as Begunov and Rollin have.

Fourthly de Michelis spectacularly fails to admit context into his theory - although he does mention it in passing - as to the origin of the Protocols: this is very important for understanding any historical event and particularly one so controversial as the origin of the Protocols. That the Protocols were written and then appeared at a time of instability and flux in the world as well as in the Russian Empire is central to understanding what the Protocols are, who potentially wrote them and also why they had an increasing amount of explanatory power.

If we admit the fact that the jews were a very active element of this instability and flux (particularly in the Russian Empire): then it indicates that there is no reason for a simple ascription of the Protocols to anti-jewish authorship, because jewish authors were similarly looking for solutions to the jewish question and could just have easily come under the influence of then current ideas about Masons and secret conspiratorial societies being the way to change things (much as Trotsky did at about the same time I might add).

Also, it is not outside of the realms of possibility that jews may have copied ideas from anti-Semitic authors and incorporated them into their own strategic vision. Much as we know that the Protocols mirrors Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat', (82) which according to both Cohn's and de Michelis' models is part of an inexplicable mass plagiarist methodology. Can we not then turn this round and suggest that the inverse is also possible in that the 'plagiarisms' - when they cannot be ascribed to later additions and redactions - could be seen as the transmission of ideas from anti-jewish authors to jewish ones (in much the same conceptual process as the hypothesized transmission of Mithraic festivals and ideas into early Christianity in the Roman Empire)? Or as de Michelis himself puts it - (83) following Segel - (84) anti-Semites have tended to use the Protocols as a blueprint for how they themselves should operate: so why could not the jews do the same with anti-Semitic literature prior to the Protocols?

This example illustrates that it is perfectly possible for two warring groups to actually use each other's ideas in modified form and as such it is perfectly feasible that this what we could be looking at here: jews having read anti-jewish texts, imbibing some of the ideas and transliterating them into a document of their own. Thus, we can see that we do not need to automatically ascribe the authorship of the Protocols to anti-Semites and can easily show that the jews are just as viable candidates for having written them.

Having thus dealt with de Michelis' argument of a Russian/Ukrainian 'satirical' origin for the Protocols: we can finally begin the process of outlining what the probable origins of the Protocols are.

The Zionist Protocols

Theodor Fritsch famously called the Protocols 'Die Zionistischen Protokolle' echoing Ludwig Mueller von Hausen's estimate of them based upon the theory as to their originating from Theodor Herzl in the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897. (85) Now this in contrast to popular myths circulated about the Protocols actually has a basis in fact in so far as numerous passages of the Protocols have been noted to potentially derive - or in terminology the literature likes to use 'plagiarise' - from Theodor Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat'.

I take issue with Taguieff's conclusion (86) that because Herzl's mentions of the jews are 'positive' in 'Der Judenstaat' and the Protocols turn these into 'negative' references; we cannot ascribe a Zionist origin to the Protocols. My issue with this is quite simple: in so far as Taguieff does not recognise the extent of the additions and redactions from the text and concentrates on the Nilus edition more than he does the Krushevan edition. Thus, his focus is somewhat distorted and his study needs to be revised in the light of de Michelis' analysis of the transmission of the Protocols before it can be seriously considered. (87)

In addition to this I would argue that assigning the subjective label of positivity and negativity in regard to the Protocols is rather misleading in so far as it removes the Protocols from their context. As if the Protocols were based on a Zionist document - which de Michelis styles document Q (equals the German term 'Quelle' or literally 'Source') - and that the Krushevan edition is a redaction of this original (as de Michelis asserts) then we are seeing the sense of the original document being redacted to fit Krushevan's worldview. (88) This necessarily means that the published edition would have a switch in its positivity in that it is summarising and quoting an original document in a negative form by changing the context in which something is said.

To give an example of this process in the inverse (i.e., an anti-Semitic comment becoming a jewish comment) what I have termed the Goldwin Smith quotation will serve.

Where the original quote from Goldwin Smith is: (89)

'The Jew alone regards his race as superior to humanity and looks forward not to its ultimate union with other races, but to its triumph over them all and to its final ascendancy under the leadership of a tribal Messiah.'

Which was modified and transmitted by one anti-jewish tradition as:

'Listen to the Jew, Goldwin Smith, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University, October 1881, “We regard our race as superior to humanity, and look forward not to its ultimate union with other races, but its triumph over them.”'

And then modified to:

'We Jews regard our race as superior to all humanity, and look forward, not to its ultimate union with other races, but to its triumph over them.

Goldwin Smith, Jewish Professor of Modern History at Oxford University, October, 1981'

It is clear here that with a few words having been changed; an original quotation's outlook on its subject - specifically jews - can be changed to the inverse of what it was previously: this is particularly true if we are dealing with something of an open tradition; like Russian anti-jewish circles of this time, which did edit documents to make them fit their ideas better. (90)

We also need to remember that if we are dealing with an open tradition with multiple additions and redactions as well as no clear source of the original text: then we cannot use normal methods of textual criticism - such as those used by Taguieff - precisely because we may well be dealing with substantially modified ideas and quotes that mean the complete opposite of how they were originally intended.

Therefore I would argue that the fact that the Protocols contains near direct quotes from Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat' as opposed to the alleged paraphrasing of Joly is actually evidence that we are here dealing with something that originally appeared in the source for the Krushevan edition as opposed to text that was later arguably added to the Protocols.

If this is indeed true, then we need to realise that this does raise the very real possibility that the source of the Protocols is a document that derives from Zionism: since as de Michelis has correctly pointed out 'Der Judenstaat' envisions a dictatorial/autocratic type of jewish government and that Herzl's transition to thinking in terms of a 'democratic' jewish state only occurs later in his novel 'Altneuland'. (91)

Now while it is indeed possible that anti-Semites used Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat' to give credence to their alleged forgery: it is unclear as to why they would go to the trouble of copying out direct quotes from it and then paraphrasing Joly's 'Dialogues' as well as the numerous works that have been alleged to have been plagiarised to create the Protocols (which - as Bolton rightly observes - actually demolishes the whole 'plagiarism' argument on the grounds of common sense). (92)

It just doesn't follow that a 'satire' or 'forgery' would be quite so illogical as to plagiarise one source directly and then steal lots of other quotes from additional sources (some jewish and some not) that would then be paraphrased when the 'satire' or 'forgery' would be more effective if it simply quoted these sources as being examples of what it has achieved (a-la the original 'translators note' concerning Darwin, Nietzsche and Marx, which Nilus then added into the text of the Protocols). Also why did they only plagiarise Herzl and why not other jewish Zionist sources that we know they had access to?

We can see then the problems for the anti-Protocols arguments simply multiply when we ask awkward pertinent questions about the conclusions that they have reached from their study of what we know about the Protocols.

Thus, because the Protocols quotes Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat' directly and paraphrases all its other 'plagiarisms' we can see that Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat' was likely part of the source document for the Protocols and that therefore it was either some kind of anti-Semitic dissertation linking ideas on power-politics and Zionism together or it is a jewish document likely of Zionist origin.

The former is plausible, but we have no actual evidence - circumstantial or otherwise - to suggest that it is the case (other than the wishful thinking of the anti-Protocols side of the debate), but in the latter case we have circumstantial evidence to point to such a conclusion.

That evidence we can derive from the context in which the Protocols came to light as we can accurately date the origin of the Protocols to between late 1901 and early 1903 given the references to world events (such as the assassination of President McKinley in 1901). (93) This combined with the Ukrainianisms in the Krushevan edition gives us a very specific locale and time period: late 1901 to early 1903 in the general area of and/or close to the Ukraine.

Now the Ukraine at this time was a tinderbox of conflict between revolutionary jewish movements - both Zionist and Marxist - and anti-jewish movements associated with anti-jewish Ukrainian nationalists or the famous 'Black Hundreds' (who actually opposed each other as well). This means we have a situation where radical political and intellectual programs are likely to have been put forward and adopted: as well as a climate of 'learning from your enemies' where anti-jewish ideas would have filtered into jewish thought and vice versa.

Then on 6th and 7th April 1903 we have the famous Khisinev pogrom (next to the Ukraine and now in Moldova) that was conducted by locals against the jewish population on the charge of the jews having ritually murdered a young Christian boy in a town slightly to the north and poisoning a Christian girl in a jewish hospital. This violent rising of the Russian workers and peasants against the jews was egged on and pushed further by a widely-read local newspaper entitled 'The Bessarabian' whose publisher and leading light just so happened to be Pavel Krushevan: the first publisher of the Protocols. (94)

Now we know quite a lot about the Kishinev pogrom and that it was close to a major centre of Zionist activity – the city of Odessa - (95) where Vladimir Jabotinsky gives his first lecture on his extreme Zionist variant Revisionist Zionism on 7th April 1903 after hearing about the pogrom. (96) We know that for example a large number of jewish Torah scrolls were desecrated and that the pogromists took a large quantity of money, goods and objects from the jews during the pogrom itself. (97)

Now with a direct connection to the first editor of the Protocols, a major centre of the Zionist movement in the Russian Empire (where extreme variants - like Revisionist Zionism - were forming) and that we know objects of importance to jews were either damaged or taken. We can make a rather revolutionary suggestion: the source document that the Krushevan edition was based on was actually taken from the Khisinev pogrom and that it was some kind of Zionist document or local plan.

This is not quite so outlandish as it might at first sound given that we know of several supporting facts for just such a source origin.

The first is all that I have just stated and in particular the proximity to Odessa - which as I have stated was a major centre of the Zionist movement - and the singular use of direct quotes from Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat'.

The second is that in September 1902 there was the 'Pan-Russian Zionist Congress' in Minsk, which included moderate as well as extreme Zionists from all over the Ukraine and the southern Russian Empire. (98) This would have meant that there was a drive to write down various ideas and concepts for discussion, which at a Zionist conference would have included heavy quotation of Herzl, which explains the direct quotes as opposed to the paraphrasing that is otherwise used.

The third is that Krushevan - as the celebrated local publisher and a well-known critic of the jews - would have been the first port of call for any pogromist who had found something they considered to be important but did not want to hang on to as at that time the authorities - who considered the pogrom an international embarrassment (although jews have consistently claimed it was an anti-Semitic conspiracy by the central government) - were actively prosecuting those involved. (99)

It is thus reasonable that they would have given the incriminating evidence to Krushevan who could then spirit it away to friends like Menshikov and Butmi: outside of the sphere of the official investigation by the authorities from Odessa which was then being conducted.

The fourth is that Krushevan would have had to publish the Procotocls away from the Ukraine and Bessarabia: precisely because of this official investigation which was focused on his role as an instigator of the pogrom locally and as such it would have aroused an official investigation if he had come forward with the source document for the Protocols at this stage which would have inevitably led to his being put on trial for complicity in the pogrom as well as the trial of his human source for similar charges as well as theft. (100)

We should remember here that each of the twenty-two pogromists brought to trial in relation to the Kishinev pogrom were charged separately (rather than as a group) and would stand trial not as a group, but as separate individuals: this would allow further charges to be easily brought by the ensuing investigation. (101) One that I might add would almost inevitably result in the conviction and punishment of Krushevan and his human source for stealing such a document from the jews irrespective of the document's contents.

That means in effect that if Krushevan published the source document from which the Protocols comes it would have meant certain punishment as it is unlikely that Krushevan did not know of the substantial diplomatic pressure being placed on the Russian Empire by the United States - at the behest of a jewish minority (102) that was growing in power and was already utilizing the scare tactics they later adopted (as a group) of exploiting gentile innocents to bolster and front their causes - which he would have interpreted as part of a jewish attempt to revenge itself on him and others associated with the Kishinev pogrom as well as the 1903 Gomel pogrom in Belarus, (103) which occurred at about the same time as the Protocols were published in 'Znamia'. (104)

'Znamia' was located outside the jurisdiction of the court of Odessa (published as it was in Petrograd) and to legally attack Krushevan the court of Odessa would need to go through the higher levels of the Russian government from which Krushevan could expect - as a patriotic anti-jewish publisher - an amount of the legal protection that would be more difficult to exercise locally in a major centre of jewish influence in the Russian Empire: Odessa.

If we bear this in mind we can see that we have a fairly good circumstantial case (and we must bear in mind that any case assigning an original source for the Protocols is inevitably based on circumstantial evidence and/or is speculative) for assigning the source document for the Protocols to a local jewish group or individual - that was likely associated with Zionist thought - and that this source document was then transmitted through another one of Krushevan's publishing channels out of concern for the well-being of his source and/or himself.

Such an origin for the Protocols also neatly explains several problematic issues that are difficult to explain from a conventional perspective all at once.

To wit: (105)

A) The 'open tradition' of the document and why several individuals (notably Krushevan, Nilus and Butmi) - if we follow de Michelis' reconstruction - seem to give us several different versions of the same basic text. If the document's providence was unclear when it reached them then it explains why they both believed but rephrased the document to meet their own ideological needs and priorities.

In essence our three editors knew of the original source document and because its providence was unclear - only deriving as 'something recovered' from the jews (a-la Krushevan's original commentary) - they sought to utilize it by adding to and redacting it to fit the type of jewish conspiracy they argued in their work was a reality. Hence Krushevan's note about the supposed Masonic origins (which are not in the actual text), Nilus' removal of the Old Testament references and insertion of Masons into the text in addition to Butmi's playing up of the age of the conspiracy (using specifically Orthodox Christian dating) and downplaying a Zionist role in it.

This also accounts for why Krushevan's edition is likely the closest to the original source of the Protocols in so far as it retains much of the structure of a series of drafted policy ideas and ideological priorities (hence the numbering system [a-la 'Protocols'] of self-contained but linked ideas), which include the Ukrainianisms because that is how the original text had been drafted and Krushevan simply published the document as he received it with a few alternations (suggested by cross-referencing against the specific language used by the Nilus and Butmi editions).

B) The contradictory explanations given by Nilus for the origin of the Protocols and his receiving a copy of them; likely a copy of the source document, from an ex-Major Sukhotin which is also mentioned by General Stepanov, and which is the one difficult point of the 'Paris origin' testimony to explain. This would potentially explain why Nilus contradicts himself in that he says he received the Protocols in either 1901 or 1905 as he is thinking of when first published his predictions of a jewish anti-Christ (1901) and when he received his copy of the source document that later became central to his vision of this jewish anti-Christ (1905). It also neatly explains - if we suppose that Stepanov is somewhat correct - why he also mentions an ex-Major called Sukhotin in that this individual was helping disseminate the source document of the Protocols to interested parties and also explains Rachkovsky's involvement in doing precisely the same thing in 1905.

C) The idea of a Zionist origin - noted by Ljutostansky in 1904 (although as stated in fact written in late 1903) - is thus vindicated as Ljutostansky was ideologically close, but not directly associated with Krushevan and could easily have found out (as he was a major compiler of material against the jews) that Krushevan's original was a Zionist publication.

This also explains why in later versions Nilus was convinced that the Protocols was a Zionist document stolen from France, while Butmi though that it was in fact a Masonic document: precisely because while both had received information of the tradition of its being something to do with Zionism: Nilus had integrated this into his world-view of a coming jewish anti-Christ while Butmi insisted on seeing in it a Judeo-Masonic plot against Russia which was in tune with what his associate Krushevan had originally thought.

D) The confusion about the alleged French origin of the Protocols. In that the idea propounded by Krushevan in his commentary alleged that the Protocols were a jewish document linked to the Freemasons - in spite of the presence of no such indicators in the original text - (that was then followed by Butmi) in addition to Ljutostansky's and Nilus' argument (which I take as representative of what Major Sukhotin told Nilus [which then Nilus then later enlarged on to include Theodor Herzl]) that it was a Zionist document recovered from the jews.

This then gives us the origin for why Radziwill, du Chayla and Stepanov, all give us three very different accounts of origins the Protocols and why they do not match up in terms of detail: in that all three of them are recounting very different versions of the origin of the Protocols that they were told separately.

These were a series of stories that were created by blending some of the truth into them (the theft and involvement of the local Russian police [who were in favour of Kishinev]) (106) but using a bigger canvas (to broaden the meaning and appeal of the Protocols [as an international Zionist or Masonic agenda is a very different beast to a local Zionist extremist's proposals] and distract attention away from their origin in southern Russia) to remove Krushevan from having to explain where he had acquired them and thus directly admitting complicity in the illegal acts of the Kishinev pogromists (and avoiding a prison sentence). (107)

E) Also, we can then explain Menshikov's reference to a Protocols style document existing in April 1902, which he may have heard of in relation to the 'Pan-Russian Zionist Congress' already mentioned and would explain both his belief in the possibility of such a document existing as well as his scepticism about whether it could in fact be found. It may also explain Menshikov's later disbelief of the Protocols precisely because he did not believe such a document could have been captured and it is unlikely that Krushevan would have told him the true origin of such a document. (108)

Thus, we can see that if we remove the myths and legends surrounding the Protocols and then place them in their historical context using what we know about them: we can actually narrow down what the source for the Protocols originally was. To wit a jewish document recovered from Kishinev by pogromists and then given to Krushevan who then published it outside the jurisdiction of the court of Odessa, which was looking for a way to prosecute him (and for which the Protocols would have been suitable ammunition) and which is the reason why de Michelis rightly suspects the document to have come from pogromist circles (although he concludes that it was a smear on the jews in contrast to my own opposing conclusion). (109)

Having thus located the Protocols in the Zionist milieu of the southern Russia Empire we can move on to the other most common attack on the Protocols: that of the charge of plagiarism, which we need to address and explain in the light of its near universal use on the anti-Protocols side of the debate.

One Thousand and One Plagiarisms

Possibly the most common theme trotted out by the anti-Protocols camp is the alleged plagiarism of the Protocols from Maurice Joly and Hermann Goedesche (writing under the pseudonym Sir John Retcliffe): so much so that it features in every academic and popular treatise on the subject of the Protocols with the most through treatment of it being Cohn who reproduces quotation against quotation in an effort to demonstrate this is the case. (110) This is - it is frequently held - the most definitive of all anti-Protocols arguments: (111) in part because the origin of the Protocols will always be speculative pending any future discovery of any or all of the substantial pieces of the intellectual puzzle of their origins.

Now this oft-cited idea is actually a selective misstatement of the case against the Protocols that has been extensively discussed in the literature on the subject.

Firstly, a large number of the quotes that Cohn identifies are from the Nilus edition of 1905 and not from the Krushevan edition of 1903. (112) Further to this we have alleged plagiarisms being added and redacted from the text by later editions (including Nilus), but on balance the amount of allegedly plagiarised material from Joly is substantially lower in the 1903 Krushevan edition than in the 1905 Nilus edition. (113)

Secondly the Joly claim is the second accusation - not the first - of plagiarism that was made against the Protocols: the first is claimed in relation to Hermann Goedesche's 1868 novel 'Biarritz'. (114) This charge was in fact taken up before the alleged Joly plagiarism was exposed by Philip Graves of the London Times (whose editor Henry Wickham-Steed was a believer in the authenticity of the Protocols) and represents a problem to the anti-Protocols argument in that it shows a desperate international jewish community looking to invent arguments against the Protocols, which suggests that we need to be particularly careful of the 'plagiarism' charge from the outset precisely because it was politicised by the jews themselves before they had evidence to argue it cogently. (115)

Thirdly the Joly text is only the best-known text of many that the Protocols have been claimed to knowingly plagiarise and/or borrow from. I have already mentioned Goedesche's 'Biarritz', but in addition we have Eugene Sue's 'The Wandering Jew' and 'The Mysteries of Paris', Alexandre Dumas' 'Marquis de Sade', Houston Stewart Chamberlain's 'The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century' and 'The Jews', Edouard Drumont's 'Jewish France', Osman Bey's 'The Conquest of the World by the Jews' and 'The Talmud and the Jews', Benjamin Disraeli's 'Coningsby', Jacob Brafmann's 'The Book of the Kahal', Nicolo Machiavelli's 'The Prince' and Abbe Barruel's 'History of Jacobinism', which accounts for those many readers will have heard of. (116)

Fourthly - as de Michelis points out - the only text to be more-or-less directly quoted rather than paraphrased is Theodor Herzl's 'Der Judenstaat', (117) which is again not something you are usually told in the popular literature on the Protocols. (118)

This then gives us a very different picture of the whole plagiarism argument in that we are being told by a multitude of authors on the Protocols that the author or authors of the Protocols sat down and plagiarised a large number of different contemporary and classic texts to create the Protocols, which then proves the Protocols to be a fraud. We should remind ourselves once again that the number of borrowings and what is borrowed differs significantly between the Krushevan edition of 1903 and the Nilus edition of 1905. (119)

So, to simplify the picture that the anti-Protocols camp is painting for us: we have an anti-Semitic author who is either trying to defame the jews and/or writing a satire about Zionism. Who then decides the best way to achieve this is to paraphrase a large amount of material from a multitude of different works: some novels, some exposes written by jews, some anti-jewish treatises, some works of political philosophy and one anti-Freemasonry treatise.

But hang on a moment: why would the author of the Protocols do this when they could just as simply innovate from their own style of writing, based on their own theories and just crib a few ideas - as opposed to plagiarising/paraphrasing whole passages - from a book or two they had read?

In addition to this - again to simplify the picture presented by the anti-Protocols camp - they would have us believe that not only did one author (Krushevan) paraphrase (well sorry they like to incorrectly call it plagiarism with all the emotional ideas that concept evokes in readers) a large number of different works, but also that a later editor (Nilus) used the same works in addition to several new ones to add to the Protocols!

We thus end up with a case of logical fiddlesticks from the anti-Protocols camp in that their textual and literary criticism has actually landed up in their presenting not only a rather illogical series of events as logical, but also showing up the fact that they are being... for lack of a better term... very stupid.

The origin of this case of logical fiddlesticks from the anti-Protocols camp can be located in one of the lesser-known problems of textual and linguistic analysis in that if a scholar looks at a text long enough, he can find any number of paraphrases, plagiarisms and literary borrowings. This is caused - as Allegro has noted in relation to Biblical Criticism - (120) by there being a finite range of expression in any language and that therefore natural parallels - particularly when two documents are talking of similar issues - are going to happen (i.e., what we may call 'parallel textual evolution'). Not taking into account principles such as these leads to all sorts of strange theories - based on largely invented linguistic parallels - such as Jesus taking his ideas from Buddhism, most of Renan's famous parallels between Mithraism and Christianity not to mention a large chunk of Kabbalistic numerology-based mysticism.

We can use this simple principle of parallel textual evolution to remove all but three of the alleged plagiarisms/borrowings on the grounds of there being few textual parallels and that there is no 'system' to the alleged plagiarism/borrowing.

These are:

A) Hermann Goedesche's 'Biarritz'

B) Maurice Joly's 'The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu'

C) Theodor Herzl's 'The Jewish State'

However, before we move on to discuss these in turn it is important to provide the reader with an example of the alleged plagiarisms/borrowings that we have dismissed and briefly explain why we have dismissed them using the example as a short case study.

The simple example of Chabry's 1897 'L'Accaparement monétaire et l'indépendance économique’ and the 20th Protocol will serve to make my point.

The mirror texts provided are as follows.

Chabry:

'The feudal lords of international finance protect this monopoly [of loans] as a sword of Damocles suspended over the peoples.' (121)

20th Protocol (de Michelis says 19th): (122)

'The loans hang like a sword of Damocles over the heads of the governed.'

This looks similar, doesn't it?

Now let’s remove the translator's (in this case de Michelis') interpolation as to the meaning from Chabry and we get:

'The feudal lords of international finance protect this monopoly as a sword of Damocles suspended over the peoples.'

Now it is clear that this isn't quite as close as we've taken out the interpolation to suggest meaning, which makes the translation look a lot closer to the original text that it does without it.

We can note that there is no use or reference to 'feudal lords' and 'international finance' in the Protocols. In addition I would note that Chabry's original uses the context of 'the peoples' to mean the peoples of the world ('peuples du monde'), which is markedly dissimilar from the idea of 'the governed' ('les gens gouvernés') as on the one hand Chabry - in the context of the twenty-four page pamphlet this is from - is telling us that 'international finance' could use their loan-capital monopoly to get rid of problem and on the other the Protocols are telling us and that the Learned Elders will use their loan-capital monopoly to get rid of problematic goyim.

What is important here is the intent and usage of the concept: in so far as they are similar, but at the same time markedly different. If we understand this then the plagiarism theory (and indeed I suspect this was the meanings for discerning the textual parallel) largely rests on the metaphor 'sword of Damocles' - as otherwise it is normal enough French and Russian right-wing assertion for the time (bemoaning the power of Mammon over the world etc) - which unfortunately for the anti-Protocols camp is equally a common metaphor connected with the insecurity of tyrants. A metaphor that could equally come out of Thomas Hobbes for example!

To demonstrate this, we can point out that President John F. Kennedy could - on the anti-Protocols camp's logic - be said to be 'plagiarising' the Protocols or Chabry when he expressed the idea that:

'Today, every inhabitant of this planet must contemplate the day when this planet may no longer be habitable. Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.' (123)

We can thus see when the metaphor of the 'sword of Damocles' is used it almost always is expressed in a similar way to Chabry or the Protocols. This then demonstrates that what we are dealing with is not 'plagiarism' or even paraphrasing, but rather a common convergence of language and a literary reference point (i.e., parallel textual evolution).

In addition to this I should note that the relevant part of the 20th Protocol in the 1920 English translation (i.e., Nilus 1905 and 1917) reads as follows:

'Loans hang like a sword of Damocles over the heads of rulers, who, instead of taking from their subjects a temporary tax, come begging with outstretched palm of our bankers.'

Even if you assume that 'over the heads of rulers' is a later mistranslation/interpolation of/for 'over the governed' then it is clear that the passages are actually quite different and bear only a misleading superficial similarity in terms of their metaphor and subject.

No wonder the anti-Protocols camp won't cite the entire passage!

Thus, we can see with a little bit of prodding the plagiarism allegations begin to come apart at the seams.

Having thus disposed of a large portion of the anti-Protocols argument on the issue of the alleged 'plagiarisms' we can move onto the two central and frequently repeated claims: namely that the Protocols include a large number of plagiarisms/borrowing from Goedesche's 'Biarritz' and Joly's 'Dialogues'.

An important introductory comment that should be made is in-line with what Myers has pointed out (124) in so far as that in this type of document the use - or rather paraphrasing - of another document is not proof against or for the document's authenticity, while in contrast a direct quote may be potentially taken as evidence for or against.

Traditionally it is presumed - following Graves (125) and Bernstein - (126) that parallels of this kind actually 'disprove' the Protocol's originating from the jews in any way, shape or form. The logical response to that is a simple one: how so?

We can examine this with a simple thought experiment as follows:

If we have a series of minutes from an important strategic meeting of one company that make their way via surreptitious means to a rival company, but that same series of minutes is partly expressed using a series of paraphrases and metaphors from a popular business book that the author of the original minutes had recently read and been impressed by. Does that therefore mean that the minutes of the meeting concerned are invalid and not what they profess to be because terms had been paraphrased/plagiarised from that popular business book?

No: of course not.

The idea that plagiarism/paraphrasing from Joly invalidates the Protocols is essentially a tautology. As the argument of Protocols being a forgery from Joly ipso facto assumes it is made up, because it may contain paraphrases/plagiarisms from another non-cited source without explaining why the use of such paraphrases/plagiarisms from such a source makes the document itself false in any way.

Having removed this common, but nonsensical argument from consideration we can move onto the case of Goedesche's novel 'Biarritz' and its relationship to the Protocols.

Hermann Goedesche - a mid-to-late 19th century editor of the conservative Prussian daily 'Kreuzzeitung' - was a noted German author of fiction and poetry under the pseudonym of Sir John Retcliffe. Segel, for example, tries to style the origin of this having been to lend 'authority' to his work, (127) but I would argue that Goedesche's novels are more in a revolutionary conservative strain (taking a controversially strong anti-jewish stand for example) and that his position as editor of the influential 'Kreuzzeitung' was authority enough if he wished to invoke it. Also, one is forced question what unstated 'authority' a writer of poetry and fiction is supposed to derive from being an English diplomat in Segel's view?

Regardless of this: one of Goedesche's novel's 'Biarritz' - from 1868 - contains a short chapter titled 'In the Jewish Cemetery of Prague' which was then republished in anti-jewish circles under the title 'The Rabbi's Speech'. (128) 'The Rabbi's Speech' then took on a life of its own and was assumed to be an actual - rather than a fictional - report of a gathering of the princes (meaning leaders) of the twelve tribes of Israel to whom the leader of the group Rabbi Simon ben Yehudah gives a speech of not dissimilar general - but not specific - content to some of the later editions of the Protocols - notably to Butmi's 1906 edition - about the primarily economic methods the jews are using to take over the world.

This transformation from fiction to fact may have in fact been intended by Goedesche as he published a shorter and heavily revised version of the chapter 'In the Jewish Cemetery of Prague' in 1881 in the French periodical 'Le Contemporain' (alongside several other strong broadsides against the activities of the jews in Russia). (129) This version - as Bronner correctly points out - was revised to make it seem more like an actual speech rather than a work of fiction: (130) although I am not convinced that Goedesche actually intended it this way, but rather as a reworking of a popular chapter in one of his works. Given that the novel concerned ('Biarritz') had already been independently translated into Russian - for example - (131) it makes perfect commercial sense for Goedesche to publish a new version of the popular story in a popular right-wing periodical in France where anti-jewish sentiment was on the rise. (132)

Segel (133) and Wolf (134) claim that 'The Rabbi's Speech' is plagiarised by the Protocols - echoing the related expose's by Joseph Stanjek and Otto Friedrich - but base their argument on Mueller von Hausen's introduction to his 1919 German edition of the Protocols 'Die Geheimnisse der Weisen von Zion' ['The Secrets of the Elders of Zion'] not the actual text itself!

'The Rabbi's Speech' is in fact only adduced by Mueller von Hausen as evidence for the authenticity of the Protocols, but crucially not part of the document itself. Segel and Wolf however misrepresent this and claim that the Protocols themselves are 'debunked' by their alleged connection to Goedesche's 'Biarritz'. (135) In fact, if you look at the passages reproduced by Segel from Stanjek and Friedrich then one can clearly see if one compares them to the article by Goedesche in 'Le Contemporain' that in spite the different language: they are almost identical.

Therefore, what Segel and Wolf claim is that the Protocols are 'debunked' by an inserted piece of evidence in the introduction to Mueller von Hausen's translation, which they then proceed to claim is 'plagiarised' when in fact it is simply a piece of fiction that was shortened and slightly restyled by the original author for popular consumption in a French periodical. It is thus little wonder that 'The Rabbi's Speech' and the chapter from 'Biarritz' are almost identical!

We can thus begin to see that the idea that the Protocols 'plagiarise' Goedesche's 'Biarritz' is and has been admitted as incorrect by modern anti-Protocols authorities. That said the anti-Protocols camp haven't abandoned this argument entirely and have modified their opinion to the idea that Goedesche's 'The Rabbi's Speech' somehow acted as a 'prototype' for the Protocols, but then again I would point out that this is a case of parallel textual evolution precisely as they don't reflect or mirror Krushevan's 1903 or Nilus' 1905 editions in any way (even though Krushevan had published it in 'The Bessarabian' in 1903), (136) but only really enter the equation as an appendix to Butmi's 1906 edition. (137)